In this part of the extension, we wanted to explore more in-depth the Tesco Grocery dataset, and especially the link between food and children overweight prevalence.

We wanted to explore deeper the papaer and establish a stronger correlation between children’s overweight prevalence and food consumption. Indeed, we firstly thought that obesity among children and grocery shopping were strongly correlated.

Introduction and expectations

We decided to explore this part of the paper as we thought that the paper didn’t go in-depth enough. Indeed, the paper focused on how the authors aggregated the data rather than on establishing strong links between childhood obesity and grocery shopping. The authors computed the Spearman correlation between obese and overweight children at reception (4-5 y.o) and 6 y.o, and food consumption estimators (energy, nutrients, nutrients entropy).

Our goal was thus to find correct predictors to produce a machine learning model that would be able to estimate overweight prevalence, given the information of an area. As we had multiple machine learning models at our disposal and more than 200 potential predictors, we thought that we could find a machine learning model that would predict the values correctly.

Our first ML benchmarking

Choice of our predictors and target

After joining the grocery dataset with the children obesity one on the area_id, we obtained a DataFrame with 202 potential predictors and 7 labels for only 544 data points.

We had to select the correct predictors and the correct target. Indeed, our model will surely overfit with 202 predictors for a sample of size 544, and we have to focus on one target value.

The data for overweight children is more sparse than the one for obese children. Indeed, obese children are included in the overweight ones, so the overweight prevalence for children will always be greater than the obesity prevalence in the same area. That’s why we chose to use overweight children as our predictor. We now had to choose between reception (4-5 y.o. children) and 6 y.o. children. We chose to select 6 y.o. children data, as they have had more time to eat and to have weight changes because of their food consumption.

As the dataset is based in London, we decided to follow the guidelines of the National Health Service to select our predictors.

We analyzed these guidelines and discovered that there were 4 main columns we can extract from the dataset that is potential cause to obesity: calories, fat, sugar, and alcohol. As children of 6 years old are not likely to drink alcohol, we will focus on the 3 columns fat, sugar and energy_tot.

Data preprocessing

We had to sanitize our data and preprocess it. We removed NA values, and standardize our input. We then splitthe data into a train set and a test set.

Machine Learning Models

Our predictors, as well as our label target, are float numbers. Thus, it was a supervised Regression problem: we decided to benchmark our predictors on various ML algorithms related to the supervised regression problems. Those models are:

- Linear regression

- Ridge model

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- Tree

- Gradient Boosted Regression (GBR)

- ADABoost

We decided to benchmark on different models to keep the model scoring the best, and to use the R² score to compare the different models.

Result

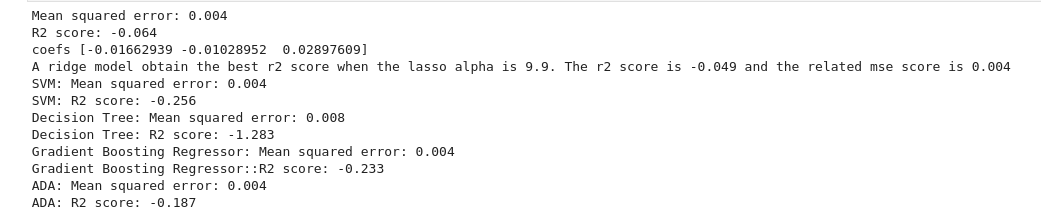

Surprisingly, our results for this ML model were not good.

We can see that the R² score is always negative, which means that our models have a worst prediction than if we stated that the target value for all of our test data was always the mean of the target values. Thus, our machine learning models predict poorly the target.

Trying out with different predictors

New predictors, same pipeline

We tried to stick with the NHS guidelines about obesity. This time, we decided to stick with the relative amount of energy for fat and sugar instead of their absolute values in the average product. It might produce different results, and we wanted to test it out.

Our predictors for this model are f_energy_sugar, f_energy_fat and energy_tot. We decided to stick with the same target, overweight prevalence for 6 y.o. children.

After sanitizing, standardizing, and splitting the data into train and test sets, we applied our ML algorithms to it.

Results and analysis

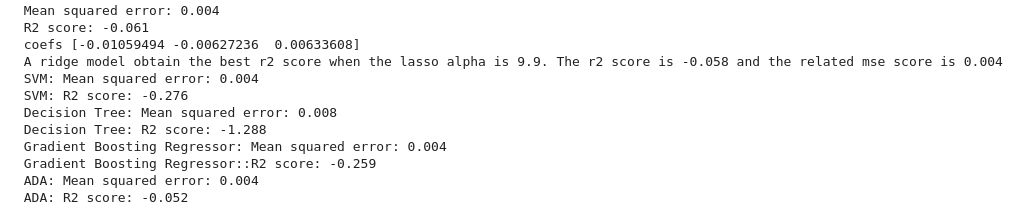

Again, our ML models predict poorly the target, as they all have a negative R² score.

But why do we have bad results while we follow NHS guidelines? Does that mean that we did something wrong?

We tried to analyze our result and explain why we didn’t find any machine learning model fitting our data.

- NHS warns about the number of calories eaten for obesity, but not for type-2 diabetes. It is because gaining weight is due to having more calories ingested than burnt. Thus, lacking some physical activity data might be more damageable for our study, as it is paramount in obesity analysis.

- We have the average product for each area, but we don’t know how much “average product” will be eaten by the children. As gaining weight is a matter of calories ingested, it is crucial information that we lack.

- We analyze children’s overweight prevalence but our data is the average product bought at Tesco. On top of the limitations pointed out in the Tesco paper (TODO: add a link to the tesco presentation blog, limitation section), we can add that we don’t know if the children eat differently than their parents.

- When babies are born, some of them weigh higher than others. It is a natural condition, that is “beaten” by one’s diet and physical activity over time. However, by capturing overweight children prevalence at 6 y.o., maybe the children haven’t lived long enough to have their eating habits changed significantly their weight.

Using food categories

We continued to work on this dataset and we wanted to try out using food categories proportions to have a correct ML model. As we decided to focus on those food categories for the other part of our extension, it made sense to use them in this project.

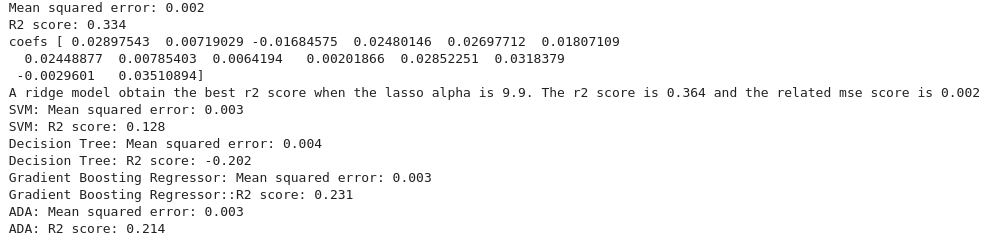

After the usual data processing and splitting, we found these results:

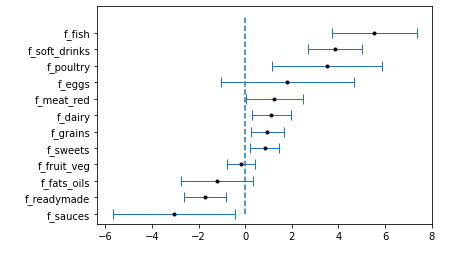

With positive R², we have done better with this third ML model than with the 2 previous ones. We decided to perform an ordinary least squares statistical analysis. After discarding the non statistically significant product categories, we plotted the result with the 95% confidence interval.

These results were quite surprising. Even though it makes sense for some food categories, for example, the soft drinks, other results are in contradiction with standard food advice. For example, we find that the highest correlated food category is fish.

Instead of overinterpreting these results, we wanted to use them to give a warning about data analysis in general. It is important for a data scientist to not try to find meaning when there’s none, as one can always find meaning if he desires. We’ll encourage young padawans to try out the Spurious correlations website for examples.

In our case, even though we have statistically significant correlations between food categories and children’s overweight prevalence, we don’t want to state that one causes another, as we don’t agree with it.

We also learnt that our intuition about correlation might be wrong sometimes. We thought that obesity among children and grocery shopping was correlated, but it was not the case.